Copyright © 2009 - 2025 Up Helly Aa Committee

The History of Up Helly Aa

Up Helly Aa is a relatively modern festival. There is some evidence that people in rural Shetland celebrated the 24th day after Christmas as “Antonmas” or “Up Helly Night”, but there is no evidence that their cousins in Lerwick did the same. The emergence of Yuletide and New Year festivities in the town seems to post-date the Napoleonic Wars, when soldiers and sailors came home with rowdy habits and a taste for firearms.

On Olde Christmas Eve in 1824 a visiting Methodist missionary wrote in his diary that “the whole town was in an uproar: from twelve o’clock last night until late this night blowing of horns, beating of drums, tinkling of old tin kettles, firing of guns, shouting, bawling, fiddling, fifeing, drinking, fighting. This was the state of the town all night – the street was thronged with people as any fair I ever saw in England.”

As Lerwick grew in size the celebrations became more elaborate. Sometime around 1840 the participants introduced burning tar barrels into the proceedings. “Sometimes”, as one observer wrote, “there were two tubs fastened to a great raft-like frame knocked together at the Docks, whence the combustibles were generally obtained. Two chains were fastened to the bogie supporting the capacious tub or tar-barrel…eked to these were two strong ropes on which a motley mob, wearing masks for the most part, fastened. A party of about a dozen was told off to stir up the molten contents.”

The main street of Lerwick in the mid-19th century was extremely narrow, and rival groups of tar- barrelers frequently clashed in the middle. The proceedings were thus dangerous and dirty, and Lerwick’s middle classes often complained about them. The Town Council began to appoint special constables every Christmas to control the revellers with only limited success. When the end came for tar-barrelling, in the early 1870s it seems to have been because the young Lerwegians themselves had decided it was time for a change.

Around 1870 a group of young men in the town with intellectual interests injected a series of new ideas into the proceedings. First they improvised the name Up Helly Aa, and gradually postponed the celebrations until the end of January. Secondly, they introduced a far more elaborate element of disguise – “guizing” – into the new festival. Thirdly, they inaugurated a torchlight procession.

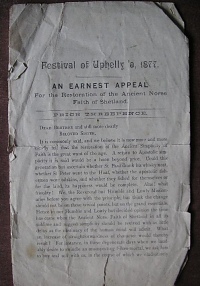

At the same time they were toying with the idea of introducing Viking themes to their new festival. The first sign of this new development appeared in 1877, but it was not until the late 1880s that a Viking longship – the “galley” – appeared, and as late as 1906 that “Guizer Jarl”, the chief guizer, arrived on the scene. It was not until after the First World War that there was a squad of Vikings, the “Guizer Jarl Squad”, in the procession every year.

Up to the Second World War Up Helly Aa was overwhelmingly a festival of young working class men and during the depression years the operation was run on a shoestring. In the winter of 1931-32 there was an unsuccessful move to cancel the festival because of the dire economic situation in the town. At the same time the Up Helly Aa committee became a self-confident organization which poked fun at the pompous in the by then long-established Up Helly Aa bill – sometimes driving their victims to fury.

Since 1949, when the festival resumed after the war, much has changed and much has remained the same. That year the BBC recorded a major radio program on Up Helly Aa, and from that moment Up Helly Aa – noted for its split-second timing before the war – became a model of efficient organization. The numbers participating in the festival have become much greater, and the resources required correspondingly larger. Whereas in the 19th century individuals kept open house to welcome the guizers on Up Helly Aa night, men and women now co-operate to open large halls throughout the town to entertain them.

For the first time in 2023, Up Helly Aa guizers were able to manage their squads in keeping with the spirit of the festival, with no gender restrictions.

The decision to relax the long-standing custom was taken by the Lerwick Up Helly Aa Committee after members discussed how to take the event forward following a two-year absence due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Despite the changes over time there are numerous threads connecting the Up Helly Aa of today with its predecessors 150 years ago.

Brian Smith